사과화상병의 생물학적 방제를 위한 효모의 탐색 및 특성 분석

; Sungsuk Oh1 ; Hyeju Jeong1 ; Je-Seung Jeon1 ; Dayeon Kim1 ; Jeong-Seon Kim1 ; In-Young Choi2 ; Jaekyeong Song1, *

; Sungsuk Oh1 ; Hyeju Jeong1 ; Je-Seung Jeon1 ; Dayeon Kim1 ; Jeong-Seon Kim1 ; In-Young Choi2 ; Jaekyeong Song1, *

초록

과수화상병은 그람 음성 세균인 Erwinia amylovora에 의해 장미과 식물에서 특이적으로 발생하는 식물 병으로 주로 사과와 배에 큰 피해를 준다. 과수화상병을 방제하기 위해 사용되는 화학약제는 병원균의 저항성 문제가 대두되면서 이를 대체하기 위해 생물학적 방제제가 요구되고 있다. 이 연구에서는 사과화상병 방제 미생물의 선발을 위해 다양한 종의 꽃과 잎, 근권 토양으로부터 효모를 분리하였다. 항균활성과 살세균활성 검정을 통해 E. amylovora 길항 효모 25균주를 선발하였다. 1차로 선발한 균주를 이용하여 미숙과와 “M9" 유묘에서 생물검정을 하였고, 그 중 가장 높은 방제 효과를 나타낸 FC-8, RJAFC2-9, TAU-3 균주를 선발하였다. 26S nrDNA 염기서열 분석결과 FC-8과 RJAFC2-9 균주는 Aureobasidium pullulans로, TAU-3 균주는 Candida vartiovaarae로 각각 동정되었다. E. amylovora에 대한 C. vartiovaarae의 방제 효과는 처음 보고되는 것으로, 과수화상병 방제를 위한 생물학적 방제제의 개발에 활용할 수 있을 것으로 기대된다.

Abstract

Fire blight, caused by Erwinia amylovora, is one of the most devastating diseases that occurs specifically in the Rosaceae family, posing a great threat especially in apple and pear orchards. Since the use of agricultural chemicals often induces pesticide resistance of Erwinia amylovora, biological control agents are proposed as alternatives. In this study, a total of 746 yeasts were isolated from various origins such as flowers, leaves, and rhizosphere soil, and screened their activity in controlling fire blight in vitro and in planta. Twenty five strains that showed both antibacterial and bactericidal effects were selected. Among them, three yeasts, FC-8, RJAFC2-9, and TAU-3, were finally selected via in planta inhibitory activity assay conducted on fruitlet and seedling of apple rootstock M9. By phylogenetic analysis based on 26S nrDNA gene sequence, FC-8 and RJAFC2-9 were identified as Aureobasidium pullulans, whereas TAU-3 were identified as Candida vartiovaarae. To our knowledge, the control effect of C. vartiovaarae TAU-3 on E. amylovora is reported for the first time, and we expect that this strain could be utilized beneficially in the development of biocontrol agents to control fire blight on the apple tree.

Keywords:

fire blight, biocontrol, yeast, Erwinia amylovora키워드:

과수화상병, 생물적 방제, 효모서 론

과수화상병은 그람 음성균인 Erwinia amylovora에 의해 장미과(Rosaceae)에서 집중적으로 발생하는 식물 병으로, 사과(Malus pumila)와 배(Pyrus pyrifolia)에 주로 피해를 입힌다(Thomson 1986; Slack et al., 2017). 국내의 경우 2015년 5월 경기도 안성에서 처음 보고된 이래 주변지역으로 확산되어 그 피해가 커지고 있다. 화상병균에 감염된 개체에서는 뚜렷한 병징이 관찰된다. 최초 감염부위에 균체와 exopolysaccharide (EPS)가 포함된 세균유출액(ooze)이 발생하고, 이후 조직 내 균 군집화와 ooze의 이동에 따라 꽃과 잎에 걸쳐 개체 전체가 불에 탄 것처럼 검게 마르며 작물 생육을 저해하고 작물 수확량을 감소시킨다(Thomson 2000; Peil et al., 2009). 또한 화분매개곤충과 비바람 같은 환경요인에 의해 전반되고, 반사물영양과 사물영양이 가능하기 때문에 확산 방지 및 감염원 제거가 어려운 것으로 알려져 있다(Thomson 1986; Sobiczewski et al., 2017).

농촌진흥청에서는 화상병의 발생 및 확산을 막기 위해 streptomycin, oxine copper, oxolinic acid 등의 성분이 포함된 항생제와 구리합성 화학물의 단제 및 혼합제 16개를 직권 등록하여 농가에 보급하고 있다(Lee et al., 2018). 그중 항생제인 streptomycin이 가장 널리 사용되는데 미국, 캐나다, 뉴질랜드, 이스라엘에서 streptomycin 저항성과 화학약제 내성을 획득한 Erwinia amylovora 균주의 출현과 그로 인한 기존 약제의 방제 효과 감소가 보고되었다(McGhee and Sundin 2011; de León Door et al., 2013). 또한 국내의 사과와 배를 비롯한 조팝나무아과(Spiraeoideae)에서 분리한 E. amylovora 다섯 균주가 유전적으로 99.5% 이상의 높은 상동성을 가지며, 유럽과 북미에서 분리된 병원균과 유전체 염기서열 평균 유사도가 99.5-99.98%라는 연구 결과가 보고되었다(Song et al., 2021). 국내에서도 항생제 저항성 E. amylovora가 출현할 가능성이 높음을 시사한다. 이와 더불어 항생제를 비롯한 화학약제 오남용의 환경오염 유발 가능성이 대두되고 있고, 화학약제의 대체 및 보조제로 생물농약이 제시되고 있다(McManus 2014). 생물농약은 저항성 병원균의 출현, 환경오염, 잔류농약으로 인한 인축독성 등, 화학농약이 가진 문제점을 해결할 수 있는 가장 좋은 전략으로 알려져 있다. 과수화상병 방제를 목적으로 상용화된 생물농약에 사용되고 있는 미생물은 Pseudomonas fluorescens A506 (Blight BanTM A506), Pantoea vagans (Blight BanTM C9-1), Bacillus subtilis QST713 (Serenade OptimumTM), Bacillus amyloliquefaciens D747 (Double NickelTM), Pantoea agglomerans E325 (Bloomtime BiologicalTM), Aureobasidium pullulans strains DSM 14940, DSM 14941 (Blossom ProtectTM) 등이 있다(Mechan Llontop et al., 2020).

효모는 생물학적 방제 미생물로서 몇몇 이점을 가진다. Biofilm을 형성하여 작물의 방어기작과 항진균제 피해를 막고, 세포벽의 멜라닌화를 통해 용균작용과 식세포작용으로 부터 방어하며, 빛, 극악한 기온, 염도, 양분결핍, 기계적 손상 등으로 인한 산화스트레스에 저항성을 가진다(Baarlen et al., 2007; Fanning and Mitchell 2012; Leal et al., 2012; Gostincar and Gunde-Cimerman 2018). 또한 가수분해 효소, 휘발성 물질, 양분경쟁, 독성물질 생성 등의 방법으로 식물병에 방제 효과를 보인 사례가 보고된 바 있다(Brakhage 2013; Gostincar et al., 2014; Di Francesco et al., 2015; Freimoser et al., 2019).

본 연구에서는 과수화상병을 방제하는 미생물을 개발하기 위해 다양한 종의 꽃과 사과의 잎과 근권 토양으로부터 효모를 분리하였고, 길항력 검정과 미숙과와 유묘에서의 생물 검정을 통해 우수한 균주를 선발하여 과수화상병의 생물학적 방제에 활용하고자 하였다.

재료 및 방법

효모 분리 및 배양

과수화상병 방제에 사용하기 위한 효모는 사과를 포함한 다양한 식물의 꽃 등으로부터 시료를 수집하여 DRBCA (Dichloran Rose Bengal Chloramphenicol Agar: Glucose 10 g, Peptone 5 g, KH2PO4 1 g, MgSO4 0.5 g, Rose Bengal 25 mg, Dichloran 2 mg, Chloramphenicol 0.1 g, Agar 15 g/1 L) , MEA (Malt Extract Agar: Malt extract 30 g, Agar 20 g/1 L), YMA (Yeast Mannitol Agar: KH2PO4 0.2g, MgSO4 0.2 g, Mannitol 10 g, Yeast extract 0.3 g, NaCl 0.05 g, Agar 20 g/1 L) , GPYA (Glucose Peptone Yeast extract Agar: Glucose 40 g, Peptone 5 g, Yeast extract 5 g, Agar 15 g/1 L), DG18 (Dichloran-Glycerol 18% Agar: Glucose 10 g, Peptone 5 g, KH2PO4 1 g, MgSO4 0.5 g, Dichloran 2 mg, Chloramphenicol 0.1 g, Agar 15 g/1 L) 배지를 이용하여 분리하였다(Kim et al., 2020). 순수분리한 효모 746 균주는 15% glycerol 1 mL에 현탁하여 -80°C 냉동고에 보관하였다. 실험 전 YPDA (Yeast Peptone Dextrose: Yeast extract 10 g, Peptone 20 g, Dextrose 20 g, Agar 15 g/1 L) 배지에 획선도말하여 28°C에서 3일간 배양해 준비하였다. YPD 액체배지에 28°C, 160 rpm 조건에서 24시간 배양하여 길항력 검정과 생물검정에 사용하였다.

E. amylovora의 배양

E. amylovora (YKB12316)는 국립농업과학원 작물보호과로부터 분양받아 사용하였다. 분양받은 균주는 cryovial (15% glycerol 1 mL)에 현탁하여 -80°C 냉동고에 보관하였다. 병원균주는 TSA 배지에 28°C에서 24시간 배양한 후 10 μl loop를 이용하여 한천배지에 있는 균체를 수확해서 준비하였다. 길항력 검정과 생물검정에 사용하기 위하여 10 mM MgSO4에 현탁한 후 1× 107 cfu/ml로 농도를 조정한 후 사용하였다. E. amylovora를 이용한 모든 실험은 국립농업과학원 농업미생물과 BL2 실험실에서만 수행하였다.

항균 활성 및 살세균 활성 효모 선발

종이 디스크 확산 검정법(Paper disc diffusion assay)을 통해 E. amylovora에 항균활성과 살세균활성을 동시에 가지는 균주를 선발하였다. E. amylovora를 0.85% NaCl에 현탁한 뒤 1 × 10⁷ cfu/mL로 농도를 조정하여 MGY (Mannitol Glutamate Yeast extract: D-mannitol 10 g, L-glutamic acid 2 g, KH2PO4 0.5 g, NaCl 0.2 g, MgSO4·7H2O 0.2 g, Yeast extract 1 g, Agar 15 g/1 L, pH 7.0)에 100 μl씩 도말하였다(Park et al., 2016). 살세균활성에 사용한 plate는 E. amylovora 희석액을 도말한 후 28°C에서 24시간 동안 배양해 준비하였다. 멸균한 8 mm 종이디스크에 효모 배양액을 60 μl 씩 점적하여 병원균이 접종된 plate에 치상하였다. 대조구로는 무접종한 YPD 배지를 동량 점적하였다. 이후 28°C 배양기에서 3일 동안 배양한 후, 길항활성이 있는 균주를 선발하였다.

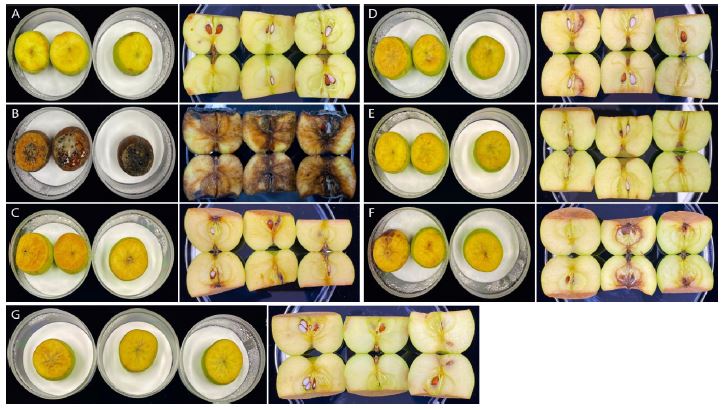

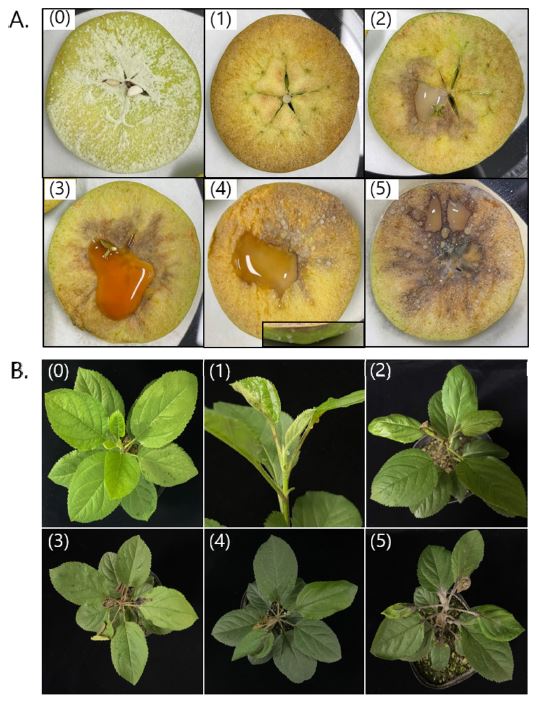

미숙과 생물검정

동시활성이 확인된 효모를 처리하여 미숙과에서의 항균활성을 확인하였다. 미숙과를 차아염소산나트륨(Sodium hypochlorite, 3%)에 3분, 70% 에탄올에 1분간 침지해 표면을 소독하고 멸균수로 2회 반복 세척한 뒤 상온에서 건조시켰다. 선발균주를 YPD 고체배지에 28°C에서 3일간 배양한 다음 10 μl loop 가득 균체를 수확하여 5 mL의 10 mM MgSO4에 현탁하여 준비하였다. 건조된 미숙과의 1/3을 잘라 단면을 균 현탁액에 30초 동안 침지하였고, 멸균수로 적신 90 mm 거름종이로 습실 처리한 100 × 40 mm 식물 배양접시에 단면이 위를 향하도록 치상하였다. 26°C 생장실에서 24시간동안 배양한 뒤, 병원균을 10 mM MgSO4에 1 × 107 cfu/mL로 조정한 희석액에 30초간 침지하여 접종하였고, 습실처리하여 26°C 생장실에서 배양하였다. 대조구로는 10 mM MgSO4를 사용하였고, 병원균 접종 17일 뒤에 발병도를 0-5단계로 나눠 조사하였다. 0단계는 미숙과 단면에 병징 미발생, 1단계는 단일 ooze 발생, 2단계는 1/4 면적에 ooze 발생, 3단계는 2/4 면적에 ooze 발생, 4단계는 3/4 면적에 ooze 발생, 5단계는 전체 면적에 ooze 발생으로 기준을 설정하였다(Fig. 1A). 이후 효모 현탁액의 농도를 OD600= 0.3(약 5 × 107 cfu/mL)으로 맞춰 2회 반복실험 하였다.

Disease severities for bioassay. Severity was classified into stage 0 to 5. A; disease severity on fruitlet, (0) no symptoms, (1) occurrence of the single ooze, (2) development of ooze on the 1/4 of fruitlet’s cross section, (3) development of ooze on the 2/4 of fruitlet, (4) development of ooze on the 3/4 of fruitlet, (5) development of ooze on all section, B; disease severity on seedling, (0) no symptoms, (1) occurrence of ooze, (2) formation of drying black on leaflet’s petiole, (3) development of symptoms on the 1/3 of a seedling, (4) development of symptoms on the 2/3 of a seedling, and (5) development of symptoms on all parts of a seedling.

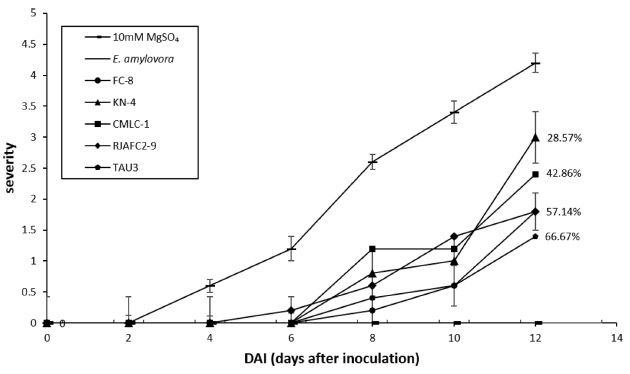

유묘 생물검정

미숙과 생물검정에서 발병도가 0단계였던 균주를 이용하여 유묘에서 생물검정을 하였다. 유묘의 품종은 화상병균에 감수성이 높은 “M9” apple (Malus domestica Borkh)을 사용하였다. 선발 효모의 처리는 10 mM MgSO4에 현탁하여 OD600= 0.1(약 1×106 cfu/mL)로 농도를 조정한 희석액을 한 개체 당 2 mL씩 골고루 분무하여 처리하였고, 26°C 생장실의 케이지 내에서 24시간 동안 배양하였다. 이후 1 × 107 cfu/mL 농도(OD600= 0.01)의 E. amylovora 현탁액을 1 mL씩 분무해 접종하였고, 26°C 생장실의 케이지에서 배양하며 12일 동안 2일 간격으로 발병도를 조사하였다. 발병도는 0-5단계로 나누어 측정하였다. 무병징묘를 0단계로 보았고, 단일 ooze 발생은 1단계, 신초의 주맥과 잎자루에 검게 마르는 병징이 발생한 것을 2단계, 개체 전체의 잎 중 1/3에 병징 발생을 3단계, 2/3에 병징 발생을 4단계, 개체 전체에 병징 발생을 5단계로 설정하였다(Fig. 1B).

효소 활성 검사

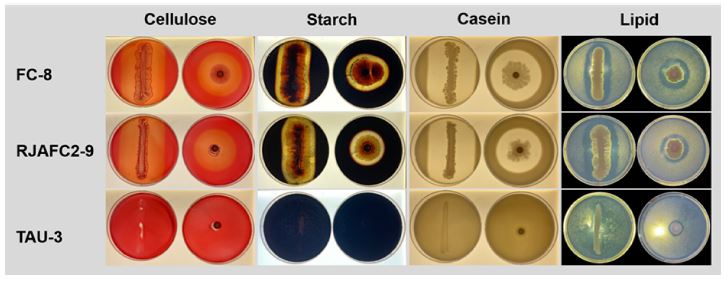

선발된 균주의 생리활성 특성을 분석하기 위해 아밀라제(amylase), 셀룰라제(cellulase), 프로테나제(proteinase), 리파제(lipase), 키티나제(chitinase), 인산가용화능(phosphate solubilization) 활성을 검정하였다. Starch (soluble starch 10 g, R2A agar 18.2 g/1 L), cellulose (CM-cellulose 20 g, R2A agar 36.4 g/1 L), casein (skim milk 100 g/1 L 115°C에 13분 멸균, R2A agar 18.2 g/1 L 121°C에 15분 멸균 후 혼합), lipid (상층: tributyrin 5 ml, R2A agar 18.2 g/1 L, 하층: R2A agar 18.2 g/1 L), phosphate (glucose 10 g, (NH4)2SO4 0.5 g, MgSO4·7H2O 0.1 g, KCl 0.2 g, MnSO4 0.01 g, Ca3(PO4)2 5 g, agar 15 g/1 L, pH 7.0) 배지를 각각 사용하였다. YPD 고체배지에 배양한 선발균주를 0.85% NaCl에 현탁한 후 8 mm paper disc에 60 μl씩 점적하여 plate 중앙에 치상하였다. 28°C 배양기에서 5일간 배양해 결과를 확인하였다. Starch는 100% 에탄올로 세척한 뒤 아이오딘 시약으로 염색하였고, cellulase는 0.1% congo red 시약으로 30분간 염색한 뒤 1 M NaCl 용액으로 15분간 세척하여 투명환을 확인하였다. Casein, lipid, chitin, phosphate는 배양 후에 바로 투명환 형성을 확인하였다. 추가로 API ZYM kit (Bio-Mérieux, France)를 사용하여 20개 효소에 대한 생성능을 실험하였다.

선발 균주 동정

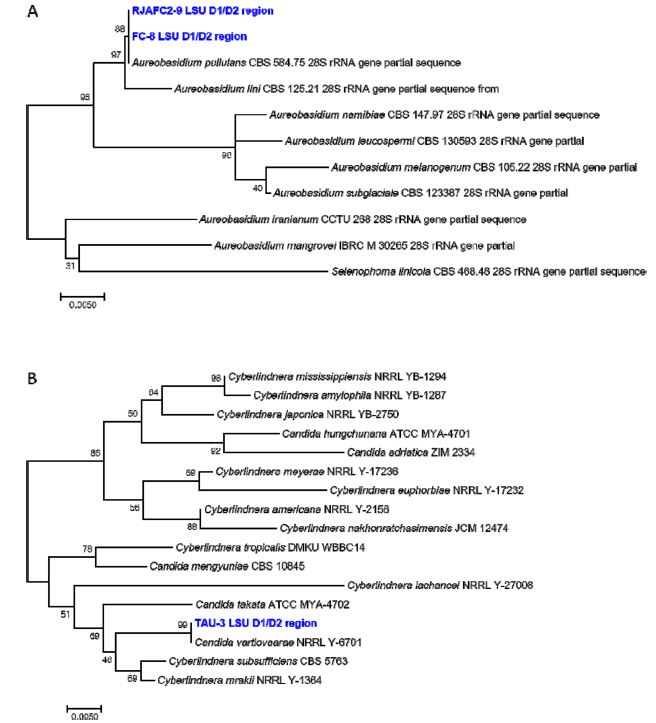

선발균주는 ㈜제노텍(대전, 한국)에 의뢰하여 26S rDNA D1/D2 영역의 염기서열을 분석한 후 계통유전학적인 분석을 수행하였다. 영역 NL1 (5’-GCATATCAATAAGCGGAGGAAAAG-3’)과 NL4 (5’-GGTCCGTGTTTCAAGACGG-3’) primer를 이용하여 26S rDNA D1/D2 영역의 염기서열을 분석하였다(Leaw et al., 2006). 얻어진 염기서열은 Seqman (DNASTAR, USA)을 이용하여 오류를 검정한 후에 조합하였고, NCBI Blast (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/)에서 관련 유전자를 검색하여 염기서열을 수집한 후 MEGA7 (ver 7.0.21) 프로그램의 Clustal W를 이용하여 염기서열을 정렬하고 Maximum Likelihood 방법으로 계통도를 작성하였다.

결과 및 고찰

E. amylovora 길항 효모 선발

분리한 746개 효모를 대치배양하여 항세균활성과 살세균 활성 검정을 실시한 결과 147 균주에서 항균활성이, 41 균주에서 살세균활성이 있음을 확인하였다. 그 중 항세균과 살세균 모두에서 동시활성을 나타낸 26 균주를 선발하였다(Table 1).

항세균활성과 살세균활성 중 하나의 활성만을 보이는 균주보다 두 가지 특성에 동시활성을 가진 균주가 화상병 억제 미생물로서 가지는 잠재력이 더 클 것으로 기대하고 선발 균주들을 이용하여 생물검정을 수행하였다. 또한 Aureobasidium pullulans와 Candida sake, Metschnikowia pulcherrima의 효모들은 이전 연구(Pusey et al., 2009)에서 과수화상병에서의 높은 길항효과가 확인되었기에 본 연구에서 선발된 26 균주도 화상병 억제 효과가 높을 것으로 생각된다.

미숙과 생물검정

항세균활성과 살세균활성을 통해 선발한 26 균주를 10 mM MgSO4에 현탁하고 미숙과에 처리하여 과실에서의 발병 억제력을 검정하였다. 발병도를 0에서 5 단계로 나누고, 병원균 접종 17일 뒤에 발병도가 0인 균주를 2차로 선발하였다. 이후 2차 선발균주의 현탁액 농도를 OD600= 0.3으로 조정하여 2회 반복실험 하였고, 그 결과 FC-8, KN-4, CMLC-1, RJAFC2-9, TAU-3의 5 균주가 세 번의 반복실험에서 모두 발병도 0단계를 나타냈다(Fig. 2). 효모는 주로 수확 후의 농작물에서 발생하는 식물병원성 진균의 생장을 억제 또는 방제하는 데 특히 높은 효과가 있는 생물학적 방제 미생물로 알려져 있다(Fredlund et al., 2002). 미숙과에서 높은 억제 활성을 보인 선발균주를 유묘 생물 검정에 이용하였다.

유묘 생물검정

미숙과에서 높은 길항력을 나타낸 5 균주를 OD600=0.1 농도로 현탁하여 “M9”품종의 사과 유묘에서 생물검정을 3회 반복하여 실험하였다. 병원균 접종 후 2일 간격으로 12일동안 발병도를 0단계부터 5단계까지로 측정하였다. 이후 병원균 접종 12일 뒤의 발병도를 이용하여 방제가를 계산하였다. CMLC-1은 42.86%로 방제가가 가장 낮았고, FC-8과 RJAFC2-9는 57.14%, TAU-3는 66.67%로 양성대조구의 발병도에 비해 높은 억제율을 보였다(Fig. 3). 최종적으로 50% 이상의 방제가를 나타낸 세 균주를 선발하였고, 선발한 균주 중 TAU-3에서 가장 높은 방제효과가 확인되었다.

TAU-3 균주는 Candida 속에 속하는 균주였다. Candida 속의 다양한 균주가 식물병을 강하게 억제하는 것으로 알려져 있으며, C. oleophila와 C. sake 등이 잘 알려져 있다(Freimoser et al., 2019). 이 균주는 수확 후 부패균인 Botrytis cinerea과 Penicillium expansum에 공통적으로 방제 효과를 나타냈다(Usall et al., 2000; Droby et al., 2002; Liu et al., 2012; Marín et al., 2016).

FC-8과 RJAFC2-9는 식물병 방제 효모로 널리 알려진 Aureobasidium 속에 속하였다. Aureobasidium 속 중 A. pullulans는 사과 푸른곰팡이병(Penicillium expansum)과 복숭아 잿빛무늬병(Monilinia laxa), 딸기 잿빛곰팡이병(Botrytis cinerea)과 같이 과실에서 발생하는 진균병에서 높은 발병 억제 효과를 나타내는 것으로 보고되었다(Adikaram et al., 2002; Bencheqroun et al., 2007; Di Francesco and Baraldi 2021). 그 외에도 A. subglaciale가 사과의 수확 후 저장 시에 저온 조건에서 발생하는 진균성 부패의 원인균인 세 가지 균주, Botrytis cinerea, Penicillium expansum, Colletotrichum acutatum에 대해 높은 방제 효과를 보이는 것으로 보고되었다(Zajc et al., 2022).

이처럼 효모는 주로 작물의 수확 후에 발생하는 진균성 식물병 방제에 높은 효과를 보여왔지만, 세균성 식물병에 대한 방제 효과에 대해서는 알려진 바가 드물다. A. pullulans 의 화상병에 대한 식물보호제로(DSM 14940 (CF10)과 DSM 14941 (CF40))균주 혼합제가 유일하게 사용되었으며, 유기농 사과와 배에 살포(Blossom Protect)하여 병을 억제하는 것으로 보고되었다(Freimoser et al., 2019, Temple et al., 2020). 가장 좋은 병 억제 활성을 보인 TAU-3 균주는 Candida 속 균주의 화상병 억제 활성을 보이는 최초 사례가 될 것이다. TAU-3 균주의 과수화상병에 대한 발병 억제 및 방제 기작에 대한 추가적인 연구가 필요할 것으로 생각된다. 본 연구에서 선발된 세 균주는 개화기의 화상병 방제에 사용할 수 있는 미생물농약의 개발에 도움이 될 수 있을 것으로 기대한다.

효소 활성 검사

선발한 3 균주의 아밀라제(amylase), 셀룰라제(cellulase), 프로테나제(proteinase), 리파제(lipase), 인산가용화능(phosphate solubilization) 활성을 실험하였다. FC-8과 RJAFC2-9는 아밀라제, 셀룰라제, 프로테나제, 리파제에서 활성을 나타냈고, TAU-3는 셀룰라제와 리파제에서 약한 활성을 보였다(Fig. 4). API ZYM 검사 결과, 세 균주가 공통적으로 Alkaline phosphatase, Esterase (C4), Esterase Lipase (C8), Leucine arylamidase, Valine arylamidase, Crystine arylamidase, Acid phospatase, Naphtol-AS-BI-phosphohydrolase, β-glucosidase에서 활성을 보였다. 또한 FC-8과 RJAFC2-9는 α-cymotrypsin, α-galactosidase, β-glucuronidase, α-glucosidase, α-mannosidase, α-fucosidase에서 양성을 나타냈으나 TAU-3 균주에서는 음성으로 확인되었다(Fig. 5). 이중 셀룰라제는 병원균의 세포벽 분해 효소로, 프로테나제는 세포벽 분해 및 병원균에 의해 생성된 가수분해 효소를 비활성화하는 기작으로 널리 알려져 선발균주의 방제 효과와도 관련될 수 있을 것으로 추정한다(Whipps 2001; Benítez et al., 2004; Loliam et al., 2013).

Hydrolysis characterization of selected strains. Yeast isolates were inoculated on media with each component to test the hydrolysis effect of cellulose, starch, casein, and lipid. The isolates, FC-8 and RJAFC2-9 have properties decomposing four components. TAU-3 can decompose only lipid.

Phylogenetic analysis of isolates, FC-8(A), RJAFC2-9(A), and TAU-3(B). The trees were reconstructed by Maximum Likelihood method based on 26S nrDNA D1/D2 hypervariable region sequence of the isolates. Bootstrap percentages (1000 replicates) are given at branch nodes. Bar indicates sequence divergence.

선발 균주 동정

효모의 종 동정은 형태적인 방법과 생리·생화학적인 방법을 사용하는 것보다 rRNA 유전자와 ITS 염기서열을 이용한 분자계통분류가 주로 사용되고 있다. 그중 D1/D2 영역을 주로 분석하여 ITS보다 더 많은 데이터베이스에 기반한다(Xu J. 2016). 본 연구에서 선발한 세 균주(FC-8, RJAFC2-9, TAU-3)의 26S rDNA D1/D2 영역의 염기서열을 확보하여 MEGA7 프로그램의 Maximum Likelihood 방법으로 계통도를 작성하였다. FC-8과 RJAFC2-9 균주는 Aureobasidium pullulans 와 100%의 높은 상동성을 보였으며(Fig. 5A), TAU-3는 100%로 Candida vartiovaarae와 높은 상동성을 보였다(Fig. 5B). 계통도의 정확도의 척도인 Bootstrap 값은 각각 88%, 88%, 100%로 높게 나타났다.

Aureobasidium pullulans는 과수화상병의 원인균인 E. amylovora에 대한 방제 효과가 확인된 바 있으나(Salk et al., 2019) Candida vartiovaarae는 본 연구에서 처음 보고되는 종이다. C. vartiovaarae TAU-3는 사과화상병의 발병 억제 효과를 보이는 새로운 균주로서 새로운 과수화상병 방제제의 개발에 활용될 수 있을 것으로 기대한다.

Acknowledgments

본 연구는 농촌진흥청 공동연구사업(과제번호: PJ015296)의 지원에 의해 이루어진 것이며 농촌진흥청과 전북대학교 간의 학연연구원 프로그램으로 이루어진 것입니다.

이해상충관계

저자는 이해상충관계가 없음을 선언합니다.

References

-

Adikaram NK, Joyce DC, Terryc LA, 2002. Biocontrol activity and induced resistance as a possible mode of action for Aureobasidium pullulans against grey mould of strawberry fruit. Australas. Plant Pathol. 31(3):223-229.

[https://doi.org/10.1071/AP02017]

-

Bencheqroun SK, Bajji M, Massart S, Labhilili M, El Jaafari, et al., 2007. In vitro and in situ study of postharvest apple blue mold biocontrol by Aureobasidium pullulans: evidence for the involvement of competition for nutrients. Postharvest Biol. and Technol. 46(2):128-135.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.postharvbio.2007.05.005]

- Benítez T, Rincón AM, Limón MC, Codon AC, 2004. Biocontrol mechanisms of Trichoderma strains. Int. Microbiol. 7(4):249-260.

-

Brakhage AA, 2013. Regulation of fungal secondary metabolism. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 11(1):21-32.

[https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro2916]

-

De León Door AP, Romo Chacón A, Acosta Muñiz C, 2013. Detection of streptomycin resistance in Erwinia amylovora strains isolated from apple orchards in Chihuahua, Mexico. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 137(2):223-229.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s10658-013-0241-4]

-

Di Francesco A, Baraldi E, 2021. How siderophore production can influence the biocontrol activity of Aureobasidium pullulans against Monilinia laxa on peaches. Biol. Control. 152:104456.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocontrol.2020.104456]

-

Di Francesco A, Ugolini L, Lazzeri L, Mari M, 2015. Production of volatile organic compounds by Aureobasidium pullulans as a potential mechanism of action against postharvest fruit pathogens. Biol. Control. 81:8-14.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocontrol.2014.10.004]

-

Droby S, Vinokur V, Weiss B, Cohen L, Daus A, et al., 2002. Induction of resistance to Penicillium digitatum in grapefruit by the yeast biocontrol agent Candida oleophila. Phytopathology. 92(4):393-399.

[https://doi.org/10.1094/PHYTO.2002.92.4.393]

-

Fanning S, Mitchell AP, 2012. Fungal biofilms. PLoS Path. 8(4):e1002585.

[https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1002585]

-

Fredlund E, Druvefors U, Boysen ME, Lingsten KJ, Schnürer J, 2002. Physiological characteristics of the biocontrol yeast Pichia anomala J121. FEMS Yeast Res. 2(3):395-402.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1567-1364.2002.tb00109.x]

-

Freimoser FM, Rueda-Mejia MP, Tilocca B, Migheli Q, 2019. Biocontrol yeasts: mechanisms and applications. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 35(154).

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s11274-019-2728-4]

-

Gostinčar C, Gunde-Cimerman N, 2018. Overview of oxidative stress response genes in selected halophilic fungi. Genes, 9(3):143.

[https://doi.org/10.3390/genes9030143]

-

Gostinčar C, Ohm RA, Kogej T, Sonjak S, Turk M, et al., 2014. Genome sequencing of four Aureobasidium pullulans varieties: biotechnological potential, stress tolerance, and description of new species. BMC Genom. 15(549).

[https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-15-549]

-

Jelkmann W, Lindner A, 2008. Studies on antagonistic yeast species against Erwinia amylovora in co-culture and on apple blossoms. Acta Hortic. 793:403-408.

[https://doi.org/10.17660/ActaHortic.2008.793.60]

- Kim JS, Lee M, Kim JY, Heo J, Kwon SW, et al., 2020. Distribution and species diversity of wild yeasts isolated from flowers in Korea. Kor. J. Mycol. 48(4):475-484.

-

Leal SM, Vareechon C, Cowden S, Cobb BA, Latgé JP, et al., 2012. Fungal antioxidant pathways promote survival against neutrophils during infection. J. Clin. Invest. 122(7):2482-2498.

[https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI63239]

-

Lee MS, Lee I, Kim SK, Oh CS, Park DH, 2018. In vitro screening of antibacterial agents for suppression of fire blight disease in Korea. Res. Plant Dis. 24(1):41-51.

[https://doi.org/10.5423/RPD.2018.24.1.41]

-

Liu J, Wisniewski M, Droby S, Norelli J, Hershkovitz V, et al., 2012. Increase in antioxidant gene transcripts, stress tolerance and biocontrol efficacy of Candida oleophila following sublethal oxidative stress exposure. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 80(3):578-590.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-6941.2012.01324.x]

-

Loliam B, Morinaga T, Chaiyanan S, 2013. Biocontrol of Pythium aphanidermatum by the cellulolytic actinomycetes Streptomyces rubrolavendulae S4. Sci. Asia. 39:584-590.

[https://doi.org/10.2306/scienceasia1513-1874.2013.39.584]

-

Marín A, Cháfer M, Atarés L, Chiralt A, Torres R, et al., 2016. Effect of different coating-forming agents on the efficacy of the biocontrol agent Candida sake CPA-1 for control of Botrytis cinerea on grapes. Biol. Control. 96:108-119.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocontrol.2016.02.012]

-

McGhee GC, Sundin GW, 2011. Evaluation of Kasugamycin for fire blight management, effect on nontarget bacteria, and assessment of Kasugamycin resistance potential in Erwinia amylovora. Phytopathology. 101(2):192-204.

[https://doi.org/10.1094/PHYTO-04-10-0128]

-

McManus P, 2014. Does a drop in the bucket make a splash? Assessing the impact of antibiotic use on plants. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 19:76-82.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mib.2014.05.013]

-

Mechan Llontop ME, Hurley K, Tian L, Bernal Galeano VA, Wildschutte HK, et al., 2020. Exploring rain as source of biological control agents for fire blight on apple. Front. Microbiol. 11:199.

[https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2020.00199]

-

Park DH, Yu JG, Oh EJ, Han KS, Yea MC, et al., 2016. First report of fire blight disease on Asian pear caused by Erwinia amylovora in Korea. Plant Dis. 100(9):1946-1946.

[https://doi.org/10.1094/PDIS-11-15-1364-PDN]

- Peil A, Bus VGM, Geider K, Richter K, Flachowsky H, et al., 2009. Improvement of fire blight resistance in apple and pear. Int. J. Plant Breed. 3(1):1-27.

-

Pusey PL, Stockwell VO, Mazzola M, 2009. Epiphytic bacteria and yeasts on apple blossoms and their potential as antagonists of Erwinia amylovora. Phytopathology. 99(5):571-581.

[https://doi.org/10.1094/PHYTO-99-5-0571]

-

Schwentke J, Sabel A, Petri A, König H, Claus H, 2014. The yeast Wickerhamomyces anomalus AS1 secretes a multifunctional exo-β-1,3-glucanase with implications for winemaking. Yeast. 31(9):349-359.

[https://doi.org/10.1002/yea.3029]

-

Slack SM, Outwater CA, Grieshop MJ, Sundin GW, 2019. Evaluation of a contact sterilant as a niche-clearing method to enhance the colonization of apple flowers and efficacy of Aureobasidium pullulans in the biological control of fire blight. Biol. Control. 139:104073.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocontrol.2019.104073]

-

Slack SM, Zeng Q, Outwater CA, Sundin GW, 2017. Microbiological examination of Erwinia amylovora expolysaccharide ooze. Phytopathology. 107(4):403-411.

[https://doi.org/10.1094/PHYTO-09-16-0352-R]

-

Sobiczewski P, Iakimova ET, Mikiciński A, Węgrzynowicz-Lesiak E, Dyki B, 2017. Necrotrophic behaviour of Erwinia amylovora in apple and tobacco leaf tissue. Plant Pathol. 66(5):842-855.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/ppa.12631]

-

Song JY, Yun YH, Kim GD, Kim SH, Lee SJ, et al., 2021. Genome analysis of Erwinia amylovora strains responsible for a fire blight outbreak in Korea. Plant Dis. 105(4):1143-1152.

[https://doi.org/10.1094/PDIS-06-20-1329-RE]

-

Temple TN, Thomson EC, Uppala S, Granatstein D, Johnson KB, 2020. Floral colonization dynamics and specificity of Aureobasidium pullulans strains used to suppress fire blight of pome fruit. Plant Dis. 104(1):121-128.

[https://doi.org/10.1094/PDIS-09-18-1512-RE]

-

Thomson SV, 1986. The role of the stigma in fire blight infection. Phytopathology. 76(5):476-482

[https://doi.org/10.1094/Phyto-76-476]

-

Thomson SV, 2000. Epidemiology of fire blight. pp. 9-36. Vanneste J (Eds.). Fire blight: the disease and its causative agent, Erwinia amylovora. CABI Publishers, Oxon, UK.

[https://doi.org/10.1079/9780851992945.0009]

-

Usall J, Teixidó N, Fons E, Vinas I, 2000. Biological control of blue mould on apple by a strain of Candida sake under several controlled atmosphere conditions. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 58(1-2):83-92.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-1605(00)00285-3]

-

Van Baarlen P, Van Belkum A, Summerbell RC, Crous PW, Thomma BPHJ, 2007. Molecular mechanisms of pathogenicity: How do pathogenic microorganisms develop cross-kingdom host jumps? FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 31(3):239-277.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-6976.2007.00065.x]

-

Whipps JM, 2001. Microbial interactions and biocontrol in the rhizosphere. J. Exp. Bot. 52(1):487-511.

[https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/52.suppl_1.487]

-

Xu J, 2016 Fungal DNA barcoding. Genome. 59:913-932.

[https://doi.org/10.1139/gen-2016-0046]

-

Zajc J, Černoša A, Sun X, Fang C, Gunde-Cimerman N, et al., 2022. From glaciers to refrigerators: the population genomics and biocontrol potential of the black yeast Aureobasidium subglaciale. Microbiol. Spectr. 10(4):e01455-22.

[https://doi.org/10.1128/spectrum.01455-22]

Seohyeon Kim, Agricultural Microbiology Division, National institute of Agricultural Sciences, RDA, and Department of Agricultural Biology, Jeonbuk National University, Graduate student, Investigation, Writing original draft preparation, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8393-886X

Sungsuk Oh, Agricultural Microbiology Division, National institute of Agricultural Sciences, RDA, Examination

Hyeju Jeong, Agricultural Microbiology Division, National institute of Agricultural Sciences, RDA, Examination

Je-Seung Jeon, Agricultural Microbiology Division, National institute of Agricultural Sciences, RDA, Postdoctoral researcher, Investigation, writing-review

Dayeon Kim, Agricultural Microbiology Division, National institute of Agricultural Sciences, RDA, Researcher, antibacterial and bactericidal test

Jeong-Seon Kim, Agricultural Microbiology Division, National institute of Agricultural Sciences, RDA, Researcher, Isolation and collection

In-Young Choi, Department of Agricultural Biology, Jeonbuk National University, Professor, Conceptualization.

Jaekyeong Song, Agricultural Microbiology Division, National institute of Agricultural Sciences, RDA, Senior Researcher, http://orcid.org/0000-0002-3553-6660, Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing-review, Editing, and Project administration.