토마토 꽃과 수정용 벌집으로부터 잿빛곰팡이병 방제 길항균주 선발

초록

국내에서 생산하는 과채류에서 발생되는 잿빛곰팡이병은 명확한 생물학적 방제 방법으로 제시된 바가 없는 실정이다. 국내에서 사용 및 개발되고 있는 화학적 방제 약제의 경우 약제저항성 병원균의 출현이 지속되고 있는 상황이다. 또한 임의 기생성으로 인해 기주의 여부에 상관 없이 생존이 가능하므로 경종적 방제 또한 어려운 실정이다. 이에 본 연구에서는 토마토 꽃에 정착력이 우수한 길항미생물을 선발하기 위해 시설재배지의 토마토 화기와 벌집 시료로 미생물을 분리하여 방제균을 선발하였다. 총 6개월의 토마토 재배기간 중 꽃에서 1,004개 균주, 벌집에서 925균주를 분리하여, 잿빛곰팡이 병원균을 억제력이 우수한 6균주를 선발하였다. 선발된 6균주는 잿빛곰팡이 병원균에 대한 항균활성이 우수할 뿐 아니라, cellulase와 protease의 활성 또한 우수한 것으로 검증되었다. 선발된 균주는 Paenibacillus polymyxa로 동정 되었으며, 토마토의 잿빛곰팡이 발병률을 약 75% 감소시키는 효과를 나타내었다.

Abstract

Gray mold disease, cause by Botrytis cinerea, occurs severe damage on varieties of fruit and vegetable production, and have no a critical control method. In case of chemicals control, it is a trigger emergence of drug resistance strains due to using them continuously. In addition, the pathogen is difficult to control naturally because it is possible to survive regardless of host status. In this study, microorganisms were isolated from tomato flower and hive samples and in order to select suitable microbial control agents for tomato gray mold disease. During six-months study, we isolated 1,004 isolates from flower and 925 isolates from pollinator hive samples. Among them, 6 strains were selected based on result of antifungal activity test. The selected strains showed not only strong antifungal activity against gray mold pathogen, but also cellulase and protease enzyme activities. The selected strains were identified as Paenibacillus polymyxa. In plant assay, P. polymyxa prevented the gray mold disease occurrence near 75%.

Keywords:

Biocontrol, Botrytis cinerea, gray mold, Paenibacillus polymyxa, Tomato키워드:

생물적 방제, 잿빛곰팡이병, 페니바실러스 폴리믹사, 토마토서 론

잿빛곰팡이병원균(Botrytis cinerea)은 넓은 기주를 지닌 병원균으로 피해를 입히는 기주로는 딸기(Fragaria x ananassa), 고추(Capsium annum), 포도(Vitis vinifera), 오이(Cucumis sativus), 토마토(Solanum lycopersicum) 등 많은 경제 작물에 큰 손실을 일으키는 병으로 알려져 있다(Jarvis 1997). 특히 이 병원균에 의한 증상은 작물의 화기, 잎, 줄기 심지어 과실에 까지 발생하여 수확량을 감소시키거나 작물의 생육에 큰 영향을 미치는 것으로 알려져 있다(McKeen 1974; O'neill et al. 1997).

병이 발생된 식물체의 경우 뚜렷한 표징(sign)이 나타나기 전에 기주별로 다양한 병징(symptom)이 관찰된다. 딸기에서는 꽃잎과 잎 표면에 갈색 반점의 병징이 나타나지만, 과실에서는 갈변 되면서 무른 증상이 병징으로 나타나며 포도와 토마토에서는 과실이 연화 되면서 썩는 병징이 관찰된다(McClellan and Hewitt 1973). 병원균은 병이 진전됨에 따라 감염 부위에 잿빛으로 분생 포자를 형성하여 표면을 덮어버리는 표징이 나타나게 된다.

잿빛곰팡이병을 방제하기 위한 대책으로는 dicarboximide(3,5-dichlorophenyl-N-cyclic imide), benzimidazoles, N-phenylcarbamate계 약제를 이용한 화학적 방제가 이루어져왔다(Rosslenbroich and Stuebler 2000). 그러나 초기에는 살균제가 효과적이었으나 반복적인 사용으로 인해 다양한 종류의 살균제에 대한 저항성이 출현하면서 방제에 어려움을 겪어왔다(Rosslenbroich and Stuebler 2000). 살균제의 저항성을 극복하기 위해 식물정유(Plant essential oils)를 이용하여 살균성을 검증한 연구결과 균사의 생장 및 포자의 발아율 감소에 효과가 있음이 확인하였다(Soylu et al. 2010).

현재까지 잿빛곰팡이 병에 대하여 국내외에서 생물학적 방제균으로서 알려진 것으로는 진균에 속하는 Trichoderma harzianum과 세균에 속하는 Bacillus licheniformis 그리고 효모인 Sacharomyces cereviciae가 알려져 지속적으로 연구가 진행되어 왔으나 아직까지 소수의 세균 및 곰팡이 균주로 제한되어 있다(Elad and Kapat 1999; Parafati et al. 2015). 이처럼 소수의 균주 만으로 방제가 이루어지는 경우 생물학적 방제 방법에 대해서도 저항성을 지니게 될 수 있다. 이미 1998년에 방제균으로 알려져 있던 Trichoderma harzianum T39 에 대하여 잿빛곰팡이 병원균의 저항성이 보고된 바 있다(De Meyer et al. 1998).

잿빛곰팡이병원균은 임의기생성 병원균으로 초기의 병발생이 주로 작물의 꽃에서 시작됨으로, 꽃에서 서식하는 길항 미생물을 이용할 경우 방제 효과를 높일 수 있을 것으로 사료된다. 따라서, 본 연구에서는 꽃에 존재하는 토마토 잿빛 곰팡이병원균 길항미생물과 화분 수정 매개충에 존재하는 유용미생물을 선발하고자 실시 되었다.

재료 및 방법

토마토 꽃과 수분용 벌집에서의 미생물 분리

경상남도 농업기술원 시설재배지(ATEC greenhouse)에서 재배되고 있는 토마토 포장에서 미생물을 분리하기 위하여 2013년 11월부터 2014년 5월까지 6개월 동안 2주 간격으로 총 13회 포장에서 시료를 채집하였다. 시료의 종류로는 화기 시료와 벌집 시료를 채집하여 포장에서 50-mL falcon tube에 담은 후 냉온 보관 방법을 이용하여 실험실까지 운송하였다.

이후 1 X PBS buffer (8 g NaCl, 0.2 g KCl, 1.44 g Na2HPO4, 0.24 g KH2PO4를 먼저 살균수 800 ml 에 녹인 후, pH를 7.4로 조정, 최종적으로 1 L로 맞춤) 30 mL을 분주한 후 초음파세척기를 이용하여 시료의 표면에 존재하는 미생물을 PBS buffer로 분리시켰다(Joyce et al. 2003). PBS Buffer에 분리된 미생물 현탁액 1 mL을 멸균수 9 mL에 넣어 5번에서 7번으로 순차적으로 희석하였다. 희석시킨 용액을 ISP media No 2 (4 g Yeast extract, 10 g Malt extract, 4 g Glucose, 20 g Agar/1 L, pH 7.2 ± 0.2)와 TSA (Tryptic Soy Broth 30 g, Agar 20 g/1 L)에 100 μL 양을 도말 하였다. 이때 각 처리 구 당 3회 반복으로 지정하여 실행하였다. 도말이 완료된 배지는 28oC 배양기에서 10일간 배양하였다.

10일 경과 후 배지에서 확인되는 세균의 단일 콜로니를 각각 새로운 E-Tube에 TSB 200 μL에 풀어준 다음 28oC 진탕배양기에서 2일간 배양을 하였다. 보관 균주 제작을 위해 배양액 90 μL와 50% glycerol stock 90 μL를 96-well plate한 칸에 분주한 후 pipette으로 혼합하여 -80oC 보관하였다(Duetz et al. 2000).

분리된 미생물을 이용한 토마토 잿빛곰팡이 길항미생물 선발

PDK 배지(Potato Dextrose Broth 10 g, Peptone 10 g, Agar 20 g/1 L) 를 이용하여 Tray plate 에 각각 20 mL 분주하여 배지를 제작한 다음 96-well plate에 배양된 균주를 Replicator를 이용하여 미생물을 배지에 접종 시켰다(Andrews et al. 1983). 2일간 28oC에서 배양한 다음 4개의 미생물 colony 중앙 부분에 4-mm 크기의 잿빛곰팡이 병원균 agar block을 접종하여 1차 대치배양을 실행하였다. 5일간 대치배양을 진행한 다음 항균력을 지닌 균주들을 선발하여 PDK 배지에 3단 도말 후 2차 대치배양에 사용하였다. 2차 대치배양은 90-mm Petri dish에 wood stick으로 길이 3 cm로 네 방향으로 각 균주마다 도말 하여 3일간 28oC에서 배양한 다음 중앙에 잿빛곰팡이병원균 agar block을 접종하여 10일간 대치 배양을 진행하였다. 2차 대치배양에서 효과가 나타난 균주를 이용하여 동일한 방법으로 3차 대치 배양을 진행하였다.

선발된 균주의 16sRNA sequence를 통한 분자생물학적 동정

선발된 균주를 TSA 배지에서 삼단 도말 하여 27oC에서 3일간 배양한 다음 단일콜로니를 50 mL TSB 배지에 접종하였다. 3일간 27oC에서 진탕 배양한 다음 4,000 rpm으로 15분간 원심 분리를 완료한 후 상층액을 피펫을 이용하여 제거 하였다. 1.5-mL tube에 남아 있는 pellet을 1 mL의 CTAB buffer에 녹여 500 uL씩 두 개의 E-tube로 분할하였다. 각각의 E-tube에서는 Lysozyme solution (50 mg/mL)을 30 μL 첨가한 후 37oC에서 1시간 배양하였다. 이후 Proteinase K solution (20 mg/mL)을 3 μL를 첨가하여 65oC Hot block에서 30분간 반응 시켜 주었다. 완료된 E-tube를 상온에서 15분간 식힌 다음 500 μL의 PCI (Phenol:Chloroform: Isoamyl alcohol, 24:25:1)를 넣고 좌우로 5~7회 혼합하여 주었다. 다음 13,000 rmp으로 10분간 원심분리기를 작동 시켰다. 상층액 400 μL를 새로운 E-tube로 옮긴 후 500 μL Isoprophanol을 첨가하여 주었다. 용액이 첨가된 tube를 좌우로 7회 혼합한 다음 5분간 13,000 rpm으로 원심분리기에서 DNA를 침전시켜 주었다. 마지막으로 70% Ethanol을 500 μL 첨가하여 이전과 동일하게 원심분리기에서 반응 시켰으며 이후 E-tube 내부의 용액을 버리고 상온에서 30분~45분 가량 건조를 진행하였다. 튜브에 50 μL의 TE-buffer를 첨가하여 DNA를 녹여내고 -80oC에서 보관 하였다(Fatima et al., 2011). 16sRNA 영역을 증폭하기 위해 27F와 1492R primer를 사용하였으며 sequence는 Solgent (Daejeon, Korea)에서 진행하였다(Lane 1991).

선발된 균주의 효소활성 실험

섬유소 분해능을 검증하기 위하여 cellulase enzyme media (yeast extract 1 g, CMC 1 g, KH2PO4 4 g, MgSO4 1 g, MnSO4 0.05 g, FeSO4 0.05 g, CaCl2 2 g, NH4Cl 2 g, Agar 18 g/1 L)를 사용하였다. 단백질 분해 능력을 검증하기 위해서는 Protease enzyme media (skim milk 10 g, agar 18 g, per 1 L)를 이용하여 효소활성 검사를 실시하였다(Carder 1986). 선발된 미생물OD600 0.2를 각 배지에 10 μL 접종하여 27oC 에서5일간 배양한 후 섬유소 분해 능을 확인하기 위해 0.1% congo red 시약으로 10 mL을 분주하여 10분간 염색 한 다음 1 M NaCl 을 이용해 5번 세척하였다. 이후 4oC 에서 12시간 보관한 다음 clean zone을 확인하여 효소 분해 능력을 검정하였다. 단백질 분해 능력은 clean zone을 형성하는 것을 통해 분해 능력을 검정하였다(Berg et al. 2005).

선발 길항미생물의 잿빛곰팡이병 발병률 억제 확인

선발된 생물적방제 후보 균주의 발병억제도를 확인하고자 대조구로서 길항균과 Botrytis cinerea 미접종 처리구, B. cinerea 처리구, B. cinerea 와 길항균 동시 처리구로 나누어 실험을 진행하였다. 각 처리구 별로 5반복으로 진행하였으며 토마토 꽃5송이씩을 사용하였다. 후보 균주는 PDK 액체 배지에서 3일간 진탕 배양한 다음 OD600 0.2 농도로 희석하여 꽃 1송이당 피펫을 이용하여 100 μL씩 접종하였다. 병원균은 PDA (Potato Dextrose Broth 25 g, Agar 20 g/1 L) 배지에 agar plug 접종한 다음 10일간 배양 후 멸균수를 이용하여 포자현탁액으로 제작된 것을 사용하였다. 포자현탁액은 Hemocytometer를 이용하여 106 cfu/mL농도로 확인된 포자 현탁액을 꽃 1송이당 100 μL씩 접종 하였다(Badawy and Rabea 2009). 길항균과 병원균 동시 처리구에서는 각각의 미생물을 100 μL 부피내에 단독처리구와 같은 농도로 조정하여 피펫을 이용하여 토마토 꽃에 분주하였다. 대조구에는 멸균수 200 μL를 병원균 처리구에는 멸균수 100 μL씩을 추가로 분주하였다. 습식 처리 상태로 상온에서 10일간 발병률을 조사 하였다. 발병률(Disease Incidence, %)은 잿빛곰팡이병의 병징 혹은 표징이 나타난 것을 1로 하여 발병률(%)을 조사하였다.

결 과

잿빛곰팡이병 길항미생물 분리 및 선발

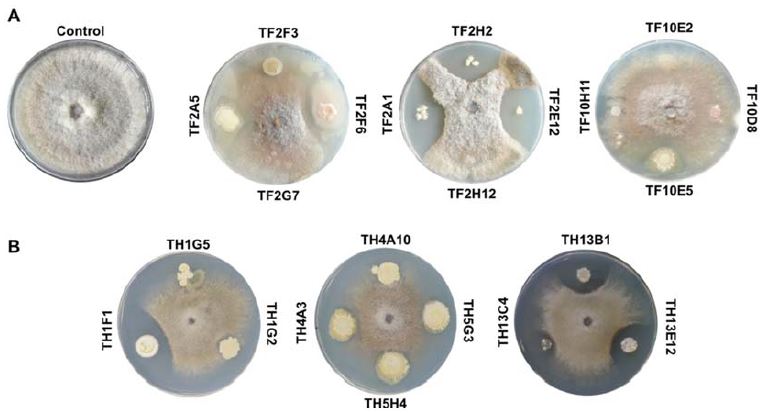

경상남도 농업기술원 ATEC센터 토마토 시설재배지에서 2013년 11월 11일부터 14일을 간격으로 2014년 5월 13일까지 토마토 화기 시료와 벌집 시료를 채집하였다. 총 13차에 걸쳐서 각각의 시료를 채집하였으며 화기 시료에서 분리된 미생물 1,004개 colony를 확보하였으며 벌집 시료에서는 925개의 미생물 colony를 확보하였다. 이후 분리된 1,929개의 미생물 colony 와 B. cinerea (KACC40574) 대치 배양을 통하여 항균력을 지닌 균주를 선발하였다. 1차 선발(Dirty and quick screen)에서는 토마토 화기 시료(TF1~TF13)로부터 258개, 벌집시료에서(TH1~TH13) 237개를 선발하였다. 2차와 3차 선발을 통하여 화기 시료에서 38개 미생물을, 벌집 시료에서는 21개를 선발하였다(Table 1). 그 중 화기 시료에서 분리된 미생물 중 항균활성능력이 가장 높게 나타낸 TF2A1, TF2E12, TF2H2, 균주의 3개의 미생물 colony를 최종적으로 선발 하였다. 벌집 시료에서는 TH1F1, TH13B1, TH13E12 균주가 잿빛곰팡이 병원균에 대하여 우수한 항진균력을 가지는 균주로 선발되었다(Table 1 and Fig. 1).

Number of isolate from tomato flower and hive. Screening of antifungal isolates against gray mold pathogen

분리된 미생물 효소 활성 실험

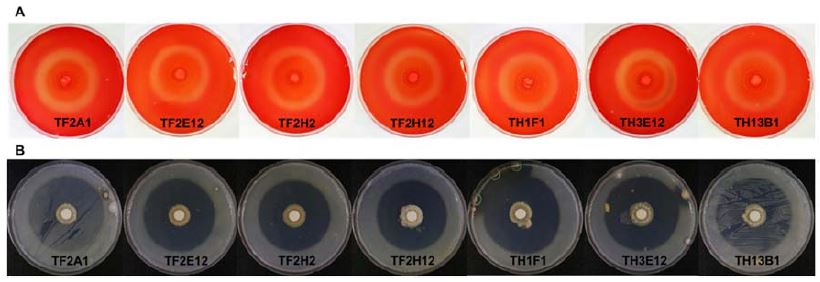

토마토 화기 시료에서 선발된 TF2A1, TF2E12, TF2H2, TF2H12 4개의 colony와 벌집에서 선발된 TH1F1, TH13B1, TH13E12 3개를 이용하여 cellulase enzyme과 Protease enzyme 활성 실험을 진행하였다. 그 결과 토마토 꽃과 화분에서 분리된 미생물들은 항균력에 상관없이 두개의 enzyme에 대하여 우수한 활성을 나타내었다(Fig. 2).

길항미생물의 동정 및 잿빛곰팡이병 발병 억제 효과

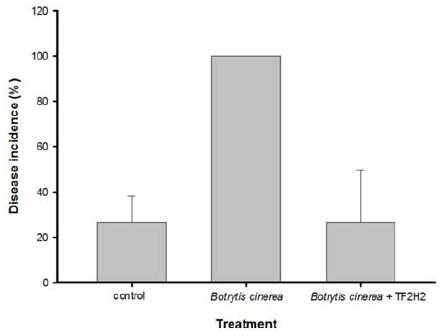

잿빛곰팡이 병원균에 대한 항진균력이 높게 확인된 선발된 6개의 미생물과 항균활성이 없는 TF2H12균주를 16sRNA sequence를 이용하여 동정한 결과 모두 Paenibacillus polymyxa로 확인되었다(Table 2). 그 중 항균력에서 가장 뛰어난 효과를 보였던 TF2H2균주를 이용하여 토마토 화기에서 잿빛곰팡이 방제 실험을 진행한 결과 잿빛곰팡이를 처리한 처리구는 모든 화기에서 100% 발병이 관찰된 반면 P. polymyxa TF2H2와 Botrytis cinerea 포자 현탁액을 같이 처리한 처리구에서 발병율이 25% 로 나타났다(Fig. 3). 동시에 멸균수만을 처리하였던 무처리구에서는 P. polymyxa TF2H2와 잿빛곰팡이 포자현탁액을 같이 처리한 처리구와 유사한 발병도를 확인 할 수 있었다.

고 찰

각종 시설재배 과채류에서 심각한 수확량 감소를 일으키는 잿빛곰팡이 병원균은 임의 기생성 병원균으로서 포장에서 재배되는 작물의 경우 식물체에서 가장 연약한 부위인화기를 통해 감염되며 과실의 저장 중에는 과실에 직접적으로 발병하여 방제가 필요한 병원균으로 인식 되어왔다. 과거부터 지속적으로 병원균의 방제를 하기 위해 살균제를 처리하였으나 균의 특성상 빠른 저항성 균주의 출현으로 인해 실질적 방제가 어려웠다(Rosslenbroich and Stuebler 2000). 이후 생물학적 방제제를 선발하여 활용하는 연구가 활발히 진행되고 있으나 대부분이 Bacillus 속 혹은 Saccharomyces 속 의 균주로서 선발된 종에 있어서 범위가 매우 한정적 이었다(Elad and Kapat 1999; Parafati et al. 2015). 작물의 재배환경, 지역, 방법 등이 다양함에 따라 길항 미생물의 종다양성이 필요한 현실이다. 이에 화기에 직접적으로 영향을 미치는 토마토 잿빛곰팡이 병원균에 대한 방제 미생물을 선발하고자 꽃과 수분용 벌집에서 후보 미생물 선발을 수행하였다. 병원균이 직접 침입하는 꽃에 잘 정착할 수 있는 길항 미생물을 확보함으로써, 잿빛곰팡이병에 대한 방제효과를 높일 수 있을 것이다. 포장 내의 화기와 벌집으로부터 총 1,929개의 colony를 분리하였으며 대치 배양과 효소 활성 실험을 통하여 화기에서 3개, 벌집에서 3개의 미생물을 선발하였다. 6개 선발미생물은 Paenibacillus polymyxa 종으로 확인되었다. 이 종은 Biofilm 을 형성하여 땅콩(Arachis hypogaea) 뿌리 썩음병을 방제한다고 알려져 있으며 검은 뿌리 썩음병을 일으키는 Leptosphaeria maculans 균에 대하여 독소로 작용하는 fusaricidin 계열을 항생물질을 분비하여 항진균력을 지니고 있으며(Beatty and Jensen 2002; Haggag and Timmusk 2008), 딸기 잿빛곰팡이병에 대하여 항진균력을 나타낸다고 보고된 바 있다(Helbig 2001). P. polymyxa 종은 병원균에 대하여 항생물질을 분비하거나 생체막 형성을 통하여 생물적 방제균으로서 사용이 가능하다고 알려져 있으며 국내에서는 Paenibacillus polymyxa GBR-1 균이 인삼(Panax ginseng)의 뿌리 썩음병을 방제한다고 보고 되었다(Kim et al. 2016). 본 연구에서 분리된 길항미생물 6종은 모두 우수한 cellulase와 proteinase 효소의 활성을 나타내었다(Table 2 and Fig 2). Cellulase 효소 활성도는 길항미생물이 식물 표면 정착력에서 영향이 있으며(Lee et al. 2015), proteinase의 활성은 병원균의 세포벽을 분해하여 직접적으로 병원균의 생장을 저해는 것으로 알려져 있다(Errakhi et al. 2007). 이에 본 연구에서는 P. polymyxa TF2H2 균이 토마토 화기에서 분리 및 확인 되었으며 잿빛곰팡이 병원균에 대하여 높은 항균력을 지니고 있으므로 본 균주의 토마토의 생물학적 방제균으로서 가능성을 제시하는 바이다.

Acknowledgments

본 연구는 농촌진흥청 차세대바이오그린21 연구과제(PJ011800)의 지원으로 수행 되었습니다.

References

-

Andrews, J. H., F. M. Berbee, and E. V. Nordheim, (1983), Microbial antagonism to the imperfect stage of the apple scab pathogen, Venturia inaequalis, Phytopathology, 73, p228-234.

[https://doi.org/10.1094/phyto-73-228]

-

Badawy, M. E., and E. I. Rabea, (2009), Potential of the biopolymer chitosan with different molecular weights to control postharvest gray mold of tomato fruit, Postharvest Biol. Technol, 51, p110-117.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.postharvbio.2008.05.018]

-

Beatty, P. H., and S. E. Jensen, (2002), Paenibacillus polymyxa produces fusaricidin-type antifungal antibiotics active against Leptosphaeria maculans, the causative agent of blackleg disease of canola, Can. J. Microbiol, 48, p159-169.

[https://doi.org/10.1139/w02-002]

-

Berg, G., A. Krechel, M. Ditz, R. A. Sikora, A. Ulrich, and J. Hallmann, (2005), Endophytic and ectophytic potato-associated bacterial communities differ in structure and antagonistic function against plant pathogenic fungi, FEMS Microbiol. Ecol, 51, p215-229.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.femsec.2004.08.006]

-

Carder, J. H., (1986), Detection and quantitation of cellulase by Congo red staining of substrates in a cup-plate diffusion assay, Anal. Biochem, 153, p75-79.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-2697(86)90063-1]

- De Meyer, G., J. Bigirimana, Y. Elad, and M. Höfte, (1998), Induced systemic resistance in Trichoderma harzianum T39 biocontrol of Botrytis cinerea, Eur. J. Plant Pathol, 104, p279-286.

-

Duetz, W. A., L. Ruedi, R. Hermann, K. O'Connor, J. Buchs, and B. Witholt, (2000), Methods for intense aeration, growth, storage, and replication of bacterial strains in microtiter plates, Appl. Environ. Microbiol, 66, p2641-2646.

[https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.66.6.2641-2646.2000]

- Elad, Y., and A. Kapat, (1999), The role of Trichoderma harzianum protease in the biocontrol of Botrytis cinerea, Eur. J. Plant Pathol, 105, p177-189.

-

Errakhi, R., F. Bouteau, A. Lebrihi, and M. Barakate, (2007), Evidence of biological control capacities of Streptomyces spp. against Sclerotium rolfisii responsible for damping-off disease in sugar beet (Beta vulgaris L.), World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol, 23, p1503-1509.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s11274-007-9394-7]

- Fatima, F., I. Chaudhary, J. Ali, S. Rastogi, and N. Pathak, (2011), Microbial DNA extraction from soil by different methods and its PCR amplification, Biochem Cell Arch, 11, p1-6.

-

Haggag, W., and S. Timmusk, (2008), Colonization of peanut roots by biofilm-forming Paenibacillus polymyxa initiates biocontrol against crown rot disease, J. Appl. Microbiol, 104, p961-969.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2672.2007.03611.x]

-

Helbig, J., (2001), Biological control of Botrytis cinerea Pers. ex Fr. in strawberry by Paebibacillus polymyxa (Isolate 18191), J. Phytopathol, 149, p265-273.

[https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1439-0434.2001.00609.x]

- Jarvis, W., (1977), Botryotinia and Botrytis Species: Taxonomy and Pathogenicity: a guide to the literature. Research Branch, Canada Department of Agriculture, Ottawa.

-

Joyce, E., S. Phull, J. Lorimer, and T. Mason, (2003), The development and evaluation of ultrasound for the treatment of bacterial suspensions. A study of frequency, power and sonication time on cultured Bacillus species, Ultrason. Sonochem, 10, p315-318.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/s1350-4177(03)00101-9]

-

Kim, Y. S., B. Kotnala, Y. H. Kim, and Y. Jeon, (2016), Biological characteristics of Paenibacillus polymyxa GBR-1 involved in root rot of stored Korean ginseng, J. Ginseng Res, 40, p453-461.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgr.2015.09.003]

- Lane, D., (1991), 16S/23S rRNA sequencing, In: Nucleic acid techniques in bacterial systematics E. Stackebrandt, M. Goodfellow Eds, John Wiley and Sons, Chichester, UK, p115-175.

-

Lee, J. H., G. Y. Min, G. Y. Shim, C. W. Jeon, and Y-S. Kwak, (2015), Physiological characteristics of actinomycetes isolated from turfgrass rhizosphere, Weed Turf. Sci, 4, p348-359.

[https://doi.org/10.5660/wts.2015.4.4.348]

-

McClellan, W., and W. B. Hewitt, (1973), Early Botrytis rot of grapes: time of infection and latency of Botrytis cinerea Pers. in Vitis vinifera L, Phytopathology, 63, p1151-1157.

[https://doi.org/10.1094/phyto-63-1151]

-

McKeen, W., (1974), Mode of penetration of epidermal cell walls of Vicia faba by Botrytis cinerea, Phytopathology, 64, p461-467.

[https://doi.org/10.1094/phyto-64-461]

-

Nguyen, X., K. Naing, Y. Lee, H. Tindwa, G. Lee, B. Jeong, H. Ro, S. Kim, W. Jung, and K. Kim, (2012), Biocontrol potential of Streptomyces griseus H7602 against root rot disease (Phytophthora capsici) in pepper, Plant Pathol. J, 28, p282-289.

[https://doi.org/10.5423/ppj.oa.03.2012.0040]

-

O'neill, T., D. Shtienberg, and Y. Elad, (1997), Effect of some host and microclimate factors on infection of tomato stems by Botrytis cinerea, Plant Dis, 81, p36-40.

[https://doi.org/10.1094/pdis.1997.81.1.36]

-

Parafati, L., A. Vitale, C. Restuccia, and G. Cirvilleri, (2015), Biocontrol ability and action mechanism of food-isolated yeast strains against Botrytis cinerea causing post-harvest bunch rot of table grape, Food Microbiol, 47, p85-92.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fm.2014.11.013]

-

Rosslenbroich, H., and D. Stuebler, (2000), Botrytis cinerea-history of chemical control and novel fungicides for its management, Crop Protect, 19, p557-561.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/s0261-2194(00)00072-7]

-

Soylu, E. M., Ş Kurt, and S. Soylu, (2010), In vitro and in vivo antifungal activities of the essential oils of various plants against tomato grey mold disease agent Botrytis cinerea, Int. J. Food Microbiol, 143, p183-189.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2010.08.015]